Romeo Is A Dead Man Spins A Violent Time Loop Through Deadford

Romeo Is a Dead Man's story begins with a sheriff’s deputy named Romeo Stargazer finding a woman in the road of Deadford, Pennsylvania. She has no memory. She asks him to kill her. He refuses. He falls in love with her instead. Her name is Juliet. The warning signs arrive early. His grandfather, Benjamin Stargazer, tells him this will end badly. Events move forward anyway.

Romeo and Juliet plan to leave town together. A creature attacks. Romeo dies. His grandfather revives him using a helmet built with advanced technology. The grandfather dies in the process, though not in any simple sense. Time fractures. Juliet disappears. Romeo becomes Deadman, sustained by the helmet and recruited by the FBI’s Space-Time Police. His task is clear: track down space-time fugitives, locate Juliet, and respond to anomalies tearing through reality.

The story runs for roughly 15 hours. It unfolds through cutscenes, comic panels, and abrupt shifts in presentation. The structure mirrors the narrative. Scenes repeat with variations. Nightmares recur. After major confrontations, credits roll before the next cycle begins. The game insists on ritual. Each fugitive requires the same steps: scan for anomalies, pilot the Space-Time Police ship called The Last Night, destroy a dimensional obstruction with a weapon named Eternal Sleep, then ride a motorcycle across a bridge of light into the mission area.

The Last Night acts as a central hub. It appears in 2D sprite form. Crew members walk its halls, including Romeo’s mother and sister alongside agents with code names. From here, missions launch. I see how the routine builds familiarity before breaking it with tonal shifts and strange detours.

Mission locations vary. One case unfolds in Deadford’s city hall. Another takes place in a 1970s cult enclave. A haunted asylum appears later. Each area becomes a 3D action stage focused on eliminating enemies and capturing a space-time criminal at the end. Combat begins with a chainsaw-sword and a pistol. Additional weapons unlock quickly. Romeo gains four melee options and four ranged firearms early in the campaign. No further tiers expand the arsenal after that point.

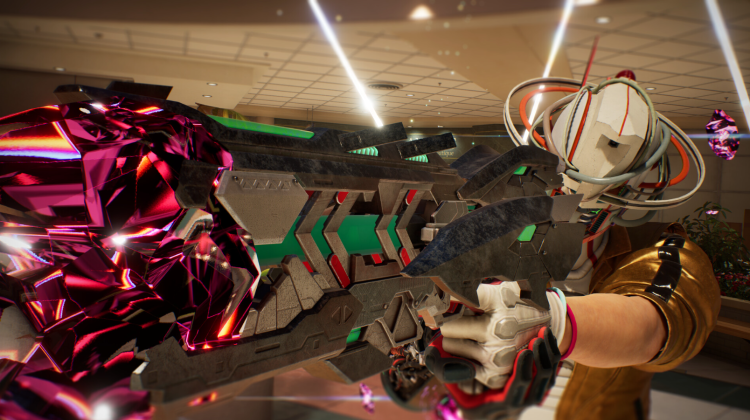

Melee combat relies on light attacks, heavy attacks, and dodges. There is no dedicated block. Attacks can chain in any order, allowing flexibility without complex move lists. Weapons differ in speed and reach. The Arcadia can split and recombine. The Juggernaut turns Romeo’s fists into heavy gauntlets. A large sword trades speed for impact. Against smaller enemies, especially the Rotters, these tools feel responsive. Hits land with force. Animations remain clear.

Larger enemies shift the balance. Many display flower-shaped weak points that open after specific triggers. Guns become essential in these encounters. The pistol, machine gun, shotgun, and rocket launcher all deal reliable damage. The rocket launcher, Yggdrasil, delivers high impact per shot at the cost of frequent reloads. Bosses and elite enemies often require targeting weak points repeatedly, which reduces the role of melee weapons during those fights.

Defeated enemies generate blood energy. This resource fuels Bloody Summer, a powerful attack unique to each weapon that also restores a portion of health. Bloody Summer can activate during jumps or dodges, adding slight variation to its use. Healing items remain limited, so managing blood becomes central to survival.

The game adopts selected elements from Soulslike design. Save points called Space-Time Pharmacies restore health and fast travel options. They also respawn defeated enemies. Death carries no currency loss. Instead, a roulette wheel grants random stat boosts such as increased attack or defense. The absence of punishment removes tension from failure, but respawned enemies extend mission length and create repetition in linear stages.

Enemy variety appears sufficient at first. Over time, patterns settle. Certain mini-bosses reappear across multiple missions. Unique space-time criminals conclude each stage, yet not all of them leave a strong impression. Some fights rely on instant-kill mechanics or extended weak-point phases. I play through several of these encounters noticing how quickly their structure becomes predictable.

Allies come in the form of creatures called Bastards. Seeds found during missions allow Romeo to grow them aboard The Last Night. These companions function as support units in battle. Some act as sentry guns. Others heal, discharge chain lightning, or rush enemies and explode. Growing them requires manual steps: appraising seeds, planting them in the garden, harvesting them when ready, and fusing duplicates for stronger variants. The system offers utility, but its importance is not emphasized early. Players who ignore it may find themselves underpowered later.

Exploration introduces subspace, a parallel dimension accessible through televisions displaying a man eating steak while delivering cryptic lines. Entering subspace overlays neon geometric paths across existing environments. Barriers in one dimension may not exist in the other. Keys found in subspace unlock doors in the main world. Combat rarely occurs here, turning these sections into navigation puzzles. Visual similarity across subspace areas can cause disorientation, especially during backtracking.

Between missions, The Last Night offers upgrades and side activities. A shop sells food and materials. Pins increase stats. Space debris refines into weapon upgrades. Cooking curry with Romeo’s mother triggers a minigame that provides temporary boosts. Leveling up requires playing an arcade-style maze game and spending collected currency. Optional challenges exist as separate combat dungeons accessed physically from the hub. Each system demands direct interaction. No shortcuts bypass these processes.

Repetition becomes thematic. Romeo wakes from recurring nightmares and knocks over a drink on his bedside table. Each fugitive case follows a fixed chain of events. Each resolution loops back into another cycle. The multiverse premise suggests variation within inevitability. The gameplay reinforces that structure by making the player perform similar tasks repeatedly. Some mechanics benefit from this consistency. Others feel prolonged without adding new layers.

Combat remains solid at its core. Weapons respond well. Enemy telegraphs stay readable. The blood system supports aggressive play. Yet depth does not expand as the story advances. By the final chapters, the same combat rhythms continue with minor adjustments.

The narrative operates in fragments. Exposition arrives in bursts, sometimes through stylized comic frames. Connections between Juliet, the fractured timeline, and Romeo’s transformation emerge gradually but never settle into full clarity. The game seems comfortable leaving gaps.

By the end, the experience feels divided. Systems interlock, though not always smoothly. Hub routines reinforce the time-loop theme. Enemy respawns test patience. Bosses range from sharp to uneven. Bastards can shift the difficulty curve if cultivated properly.

Romeo Is a Dead Man commits to its structure. It presents a world that repeats with variation, then requires the player to live inside that repetition. The result is a 15-hour action game that experiments with form while relying on familiar mechanics. Its sphere of time closes, then restarts.

3 free cases and a 5% bonus added to all cash deposits.

5 Free Cases, Daily FREE & Welcome Bonuses up to 35%

a free Gift Case

EGAMERSW - get 11% Deposit Bonus + Bonus Wheel free spin

EXTRA 10% DEPOSIT BONUS + free 2 spins

3 Free Cases + 100% up to 100 Coins on First Deposit

Comments