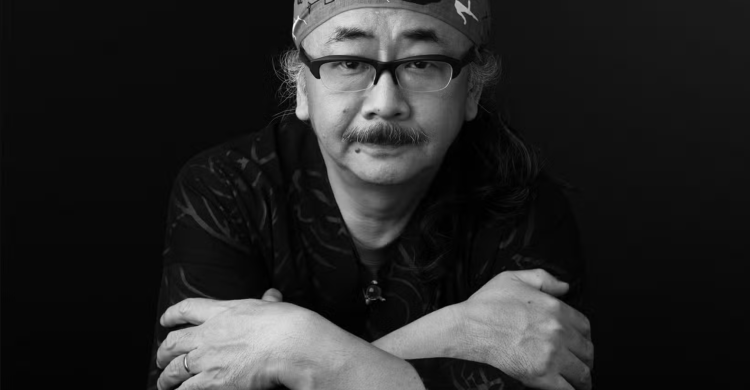

Final Fantasy Composer Nobuo Uematsu Criticizes Lack of Creative Freedom in Modern Game Music

Nobuo Uematsu, the legendary composer behind the soundtracks of the first nine Final Fantasy titles and countless other works, has spoken out once again about the state of modern video game music. Known for his genre-bending compositions and ambitious variety, Uematsu has long been celebrated as one of the most influential figures in the industry. His recent comments, however, reveal frustration at how little creative freedom game composers are given today.

Speaking with Japanese outlet Real Sound in an interview covered by Automaton and later expanded by other publications, Uematsu shared his thoughts on why game music has been trending in what he views as a restrictive direction. He avoided labeling the current state of the industry as full stagnation but emphasized the growing constraints placed on composers by directors and producers.

"I wouldn't go so far as to say that the industry is stagnant, but I do think that directors and producers have too much power in the music department," Uematsu said. "Even now, game composers aren't in a position to express their opinions very much, and no matter how much knowledge and skill they have, it's difficult to convey that." — Nobuo Uematsu

The heart of Uematsu’s concern lies in the dominance of cinematic scoring styles. According to him, many producers prefer music that emulates the sweeping orchestral style popularized by John Williams, often at the expense of originality.

"There are very few producers who are well-versed in global entertainment and various musical genres," Uematsu explained. "So it's enough to just play cinematic music in the style of John Williams. I want to do something about this situation, but the bigger the content gets, the more difficult it becomes. Personally, I'd like to see more young, energetic indie composers emerge." — Nobuo Uematsu

Square Enix has confirmed that Final Fantasy 7 Remake Intergrade will release on January 22, 2026, for Nintendo Switch 2, Xbox Series X/S, and PC, marking the series’ long-awaited debut outside of PlayStation. The Intergrade edition comes bundled with the base game and Yuffie’s DLC, giving players across all platforms the most complete version to date while setting the stage for the full trilogy.

Uematsu has previously described modern game soundtracks as “boring” or “less weird,” suggesting that much of the experimentation and eccentricity that once defined the medium has faded. He believes that an overreliance on safe orchestral scoring discourages risk-taking. To him, game music should constantly evolve, even if it means blending unexpected influences or experimenting with unconventional sounds.

In reflecting on his own work, Uematsu recalled the creative risks he took when writing themes for Final Fantasy VII, particularly its final battle track. The piece was assembled over three weeks of constant rearrangements, eventually convincing colleagues to accept his vision despite initial skepticism. This kind of persistence and creative conviction, he suggests, is what allowed his work to stand apart.

The contrast, in his view, is that modern composers are too often boxed into a framework where deviation is discouraged. Instead of striving for innovation, they are asked to deliver polished but predictable music that suits a narrow vision of what “game music” should sound like. He highlighted how mainstream soundtracks now lean heavily on sequencers and synthetic textures without breaking the mold.

“Frankly speaking, there’s less ‘weird things’ now,” Uematsu said.

Still, he sees opportunity for change. Drawing inspiration from artists like Elton John, who managed to pursue fresh creative directions even after major commercial success, Uematsu encourages today’s composers to seek out their own distinct voices. He believes that even within restrictive systems, musicians can explore new sounds and approaches. For example, blending orchestral music with electronic or techno elements could yield results that are both commercially viable and artistically daring.

This perspective fits Uematsu’s career-long philosophy. His work on Final Fantasy frequently fused genres, jumping from rock-inspired battle themes to operatic ballads and whimsical chiptune-style tracks within the same game. That eclecticism, he argues, is part of what made earlier eras of video game music so memorable. By comparison, he feels modern titles sometimes sacrifice individuality in pursuit of a cinematic atmosphere that blurs together from game to game.

Though Uematsu has stepped back from scoring full game soundtracks in recent years, he continues to follow the industry closely and remains invested in its artistic direction. He acknowledges that large-scale productions inevitably come with compromises, but he hopes that indie developers and fresh voices in the field will push boundaries in ways the mainstream often avoids.

For players who grew up with Final Fantasy’s iconic soundtracks, Uematsu’s comments resonate as both a critique and a call to action. The suggestion is not that orchestral scores are inherently bad, but that their dominance risks crowding out the diversity and experimentation that once defined game music. By urging composers to embrace the “weird” again, Uematsu points toward a future where video game soundtracks could reclaim their role as some of the most adventurous and surprising music in entertainment.

Comments