Dragon Quest I & II HD-2D Remake Review: A Classic Reborn With Modern Precision

Square Enix’s Dragon Quest I & II HD-2D Remake closes the loop on one of gaming’s foundational trilogies. It’s a project that doesn’t so much reimagine the past as polish it until the lines between nostalgia and novelty blur. Following last year’s Dragon Quest III HD-2D Remake, the new release uses the same painterly art style and fine-tuned mechanics to present the first two entries as they might exist if born today. The result feels both archival and alive—a carefully built monument to 1980s RPG design that still carries the warmth of human hands behind it.

In his review for IGN, George Yang writes that Square Enix “recaptures the retro magic of the originals while giving them a modern facelift.” He frames the remakes not as reinventions but as deliberate restorations—projects that honor the limitations and tone of their source material while quietly upgrading the experience. Both games, he notes, “still stand on their own,” bolstered by subtle additions that expand their worlds without distorting their essence.

“New content is cleverly integrated to help pad out the short run time,”

Yang observes, calling attention to the restrained scale and gentle pacing of Dragon Quest I, which now offers fresh scenes and minor quests to flesh out secondary characters such as Rubiss, the goddess of creation.

“Playing solo forced me to consider all my options and be much more methodical,”

He adds later, reflecting on the first game’s lone-hero structure and its unadorned turn-based combat that asks players to think, not rush.

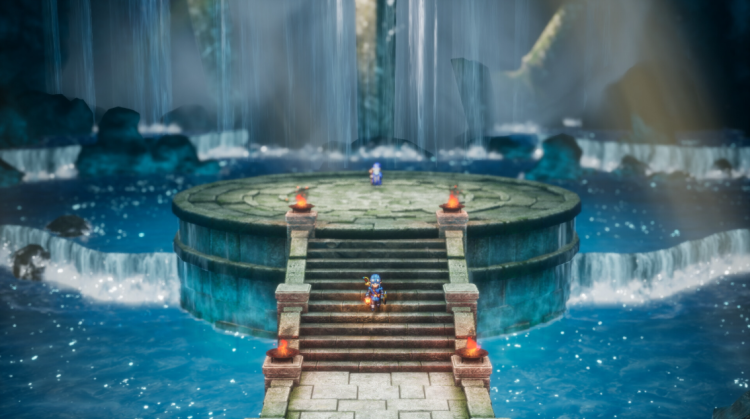

Dragon Quest I & II HD-2D Remake inherits the lush aesthetic of its predecessor, fusing expressive 2D sprites with detailed 3D backdrops. It’s a visual style now synonymous with Square Enix’s nostalgic branch, seen in Octopath Traveler, Live A Live, and Triangle Strategy. The combination gives the world depth without losing its storybook simplicity—dappled light filters across castle floors, the water shimmers faintly as if hand-brushed. It’s as though the visual design insists that old worlds still deserve to shine.

The structure of the duology mirrors its historical arc. Dragon Quest I remains a small, focused journey through Alefgard, a world of knights, kings, and the ever-looming Dragonlord. It’s an origin story in the purest sense—one hero, one evil, and a string of villages straining under the weight of myth. What distinguishes this remake is not new complexity but the confidence of its simplicity. The narrative doesn’t plead for empathy from its villains or seek moral ambiguity. It is a straightforward story about good versus evil, carried by gameplay rather than emotional ornament.

Combat in Dragon Quest I feels stripped to the bone but far from primitive. The player moves alone, striking and defending in turns that echo tabletop precision. Every decision—whether to risk an attack or take a defensive breath—becomes consequential. Without companions to absorb hits or heal, even minor battles become strategic puzzles. The addition of small tweaks, such as autosaving after fights and the return of “Draky Quest” easy mode with toggleable invincibility, softens the harsher edges without betraying the spirit of the original.

It’s in Dragon Quest II, though, that the remake’s scale and tone expand. Set a generation later, it introduces a full party—descendants of the first hero—embarking on a longer, more dynamic adventure. The change shifts the rhythm of the game: what was once solitary becomes communal. The dialogue gains texture, the tone brightens, and the world grows denser. The seas open up to exploration, now including underwater travel that reveals hidden dungeons and post-game content.

The silent protagonist is balanced by colorful companions whose interactions feel new yet timeless. Their differences are mild but human: the Prince of Cannock’s boyish optimism, the Princess of Moonbrooke’s impulsive drive for vengeance, and the Princess of Cannock’s level-headed loyalty. The remake enriches their interactions, granting new lines and moments that make them feel less like placeholders for mechanics and more like young adventurers growing into their roles.

Square Enix’s additions are modest but effective. The Princess of Cannock, barely present in the original, now fights alongside her companions as a full party member. She shares witty exchanges with her brother that bring lightness to darker scenes. These moments don’t transform the story—they ground it, reminding the player that this world, however small, contains relationships worth saving.

Mechanically, Dragon Quest II deepens the combat system through Sigils—collectible relics that provide party-wide benefits. Once useless trinkets, they now influence tactics. The Moon Sigil boosts the strength of offensive spells, while the Soul Sigil empowers attacks at low health, turning risk into potential reward. They introduce subtle decision-making: should you heal a wounded ally or let them linger at half health to deliver a stronger strike? These are not dramatic innovations but refinements that fit naturally within the series’ established grammar.

Both games benefit from universal improvements across the trilogy. The option to toggle objective markers prevents players from getting lost while preserving the possibility of pure exploration for those who prefer the old NES opacity. Mini Medals, a feature borrowed from later entries, encourage careful inspection of barrels and stones, rewarding curiosity with equipment upgrades that meaningfully impact survival. Even small details, like the sped-up battle animations, reveal a developer intent on reducing friction without diluting challenge.

The dual remakes exist as complements rather than contrasts: the first intimate and ascetic, the second broader and more intricate. Taken together, they track the genre’s early evolution—from the isolated hero’s trial to the ensemble’s collective odyssey. This structure also mirrors Square Enix’s own developmental arc across the trilogy of remakes, each entry refining the balance between nostalgia and modernity a little further.

The admiration expressed in the review feels rooted in this craftsmanship. The project is described as “the perfect sendoff to one of the best RPG trilogies of all time.” That phrasing is deliberate: not a revival, but a sendoff—a closure that respects what came before without rewriting it.

Part of the achievement lies in restraint. The HD-2D aesthetic could easily overwhelm with gloss, yet here it never smothers the 8-bit skeleton beneath. Shadows remain sharp, environments readable, and battle effects—icicles shattering midair, crimson flares trailing from sword slashes—carry the energy of modern design filtered through a retro lens. These flourishes breathe life into moments that might once have been static lines of text.

Narratively, Dragon Quest II carries the emotional weight of the collection. It's a story of familial duty and inherited legacy that folds back into the first game, creating a dialogue across generations. The Princess of Moonbrooke’s transformation—from vengeance-driven survivor to leader fighting for unity—embodies the trilogy’s quiet message: that heroism endures, not through power, but through persistence.

The game’s pacing remains deliberate. While Dragon Quest I can be finished in under a dozen hours, even with the added content, Dragon Quest II stretches closer to 25, filled with optional dungeons, seafaring detours, and post-credits quests. The balance between brevity and expansion feels intentional—an homage to the era when RPGs invited completion rather than endless continuation.

The difficulty, though, can still bite. Random encounters return, and though the autosave and easy modes offer safety nets, there are moments when luck swings brutally. Facing dragons that strike twice per turn or entering a cave ill-prepared can still wipe out progress in seconds. But these spikes serve a purpose: they remind players of a time when victory was uncertain and patience was part of the reward.

Square Enix’s care for this trilogy reaches beyond visuals or combat. It’s a study in tone—how to preserve sincerity in an age of irony. There’s no winking self-awareness, no parody of its own history. The dialogue, simple as it is, believes in itself. When characters speak of destiny or courage, they mean it. That directness, rarely found in modern RPGs that trade conviction for commentary, feels unexpectedly refreshing.

The final stretch of Dragon Quest II carries a sense of culmination. The heroes descend into a world once described only in myth, confronting an evil that’s less a surprise than a tradition. It’s not the narrative twist that satisfies but the return—the sense that these stories still matter because they remember where they began.

By the end, Dragon Quest I & II HD-2D Remake stands as both artifact and invitation. It’s a reminder of what early RPGs achieved with so little and how those boundaries still define the shape of the genre. Its improvements—small, precise, respectful—demonstrate how preservation can coexist with progress.

Square Enix’s trilogy began as an experiment in nostalgia and ends as a statement of continuity. Across three remakes, the studio has refined not only its HD-2D formula but also its understanding of why these worlds endure. It’s not the pixel art or the turn-based battles alone—it’s the sincerity of their construction, the belief that a good story, told simply and told well, doesn’t age.

Comments