Blue Prince Doesn’t Want You to Finish It

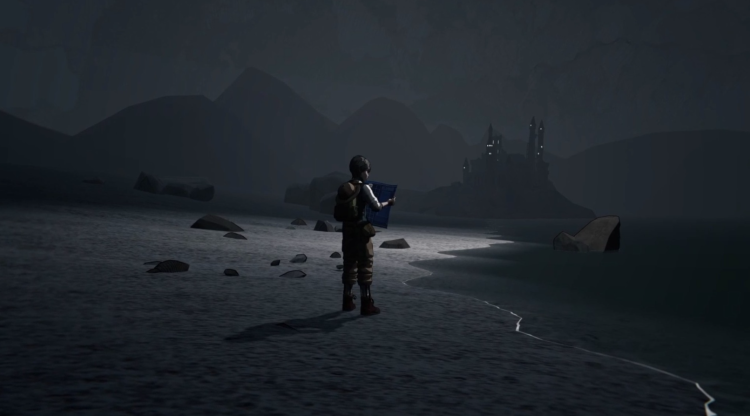

Blue Prince goes out of its way not to end. You might think you’ve reached the final stretch when you solve the cipher, unlock Room 46, or find the typewritten note addressed to Simon that cuts off mid-sentence. But every time you reach a conclusion, the game gently pushes you toward another unsolved thread. A door unopened. A puzzle left hanging. A spiral of stars that keeps growing in the sky.

At first, it seems like a normal puzzle game, just bigger and more layered. But by the time you’ve spent a hundred hours charting every inch of Mount Holly Manor, that illusion fades. What’s left isn’t a grand solution or final cutscene—it’s a quiet realization. This game was never meant to be fully solved.

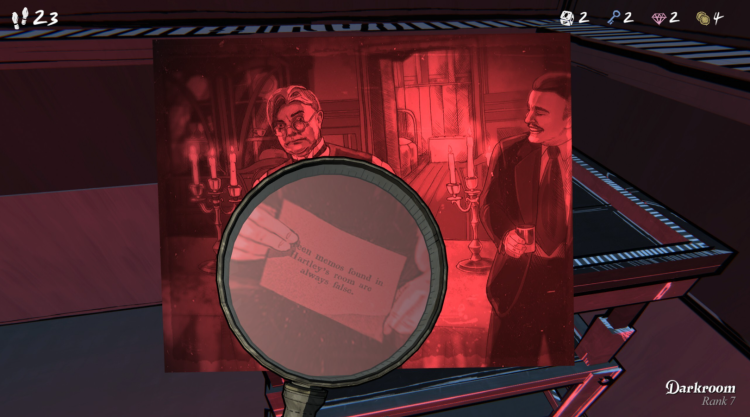

There are moments that hit with clarity. A journal entry reveals how Herbert Sinclair, architect of the manor and longtime puzzle-maker, spent decades trying to crack the same code his brother Simon couldn’t solve. He never succeeded either. Not because he gave up, but because some things aren’t meant to be finished.

You feel the weight of that while reading his notes. You feel it again when Mary’s presence—Simon’s missing mother—starts to surface through breadcrumbs left in secret rooms. Each clue is intimate, deliberate, and often leads nowhere concrete. Just new fragments. New spirals.

It’s not an accident. Blue Prince creates mystery on purpose and withholds closure on principle. It’s not a game about answers, it’s a game about what it means to not have them. That frustration, the drive to know, the inability to reach closure—is the emotional heart of the experience.

That’s what sets Blue Prince apart from other mystery or puzzle games. Even the most cryptic indie titles usually tie their threads together with enough effort. Here, the threads are woven into more threads. There are puzzles that might never be solved, and that is exactly the point.

It’s a bold decision. Games like this usually live or die by their ability to tie story and mechanics together in the end. Instead, Blue Prince mirrors something closer to real grief. You can learn so much about a person—Mary, Sinclair, Aurevei—but there will always be parts of them locked away, either lost in time or sealed behind something no one can open.

You’re supposed to feel the spiral. You’re supposed to reach the limit and still feel like you're missing something.

Even the community has reached this point. Players have rolled credits twice, seen “endings,” solved the major riddles, and still, the game resets. New notes appear. New secrets beckon. No one agrees on what the final answer is, or if one even exists.

Chris Person, in his reflection on Blue Prince, called this feeling a “metatext on puzzles and clues.” He suggested that the anticlimax isn’t a flaw—it’s a message. Some mysteries just torment you. Some puzzles are written not to be solved, but to leave you staring at them forever.

If that sounds heavy, it is. Blue Prince is not a clean experience. It messes with your instincts. It gives you the tools, then leaves you without closure. And in doing so, it tells a story most puzzle games would never attempt.

This is what makes it more than just a clever design. It’s what makes it personal. You’re not just solving for story beats or progress. You’re searching for people who are already gone. You’re piecing together echoes of a family fractured by time, death, and things unsaid.

It’s like trying to remember someone you’ve lost. The more you look back, the more you realize how much you missed. How many questions have you never thought to ask? How many answers are now out of reach?

By the time the game leaves you staring at the stars—one added to the spiral each time you look up—you understand that the story hasn’t ended. It just continues without you.

Blue Prince may be the first puzzle game designed to never be finished. Not because it’s broken, but because it’s about what breaks when people leave behind pieces of themselves. And when you follow their clues, you don’t find answers. You find absence. You find longing.

You find a message started in a typewriter that will never be completed.

And you move on.

Comments